Interventions

The practices that align with Our Ethos & Values and underpin our interventions

At Sherwood Foundation School we are proud of our individualised, transdisciplinary approach to learning; with the child/ young person and their family at the heart of our school offer. School leaders, teaching staff, wellbeing practitioners, therapists and support staff at Sherwood Foundation School work in a transdisciplinary way to provide an excellent education and to meet the provision requirements and outcomes of the EHCPs for all children and young people within the school.

Our leadership team, teachers, wellbeing practitioners and therapists all use their specialist experience, wider reading, review of current evidence based practice, links with other schools and colleges and ongoing professional training and development to ensure that we continue to provide educational and therapeutic approaches, interventions and strategies that fit comfortably with our ethos and values. This area of our website intends to summarise the practices that underpin the delivery of our education offer and the whole school approaches that we use at our school

-

Practices that underpin our school offer:

- Transdisciplinary working

- Our LEARN values

- Strengths based and person-centred practice

- Relationship focused practice

- Developmentally appropriate interventions

- Trauma informed and applied practice

- Neuroscience aligned practice

- Neurodiversity Affirming Practice

Transdisciplinary working

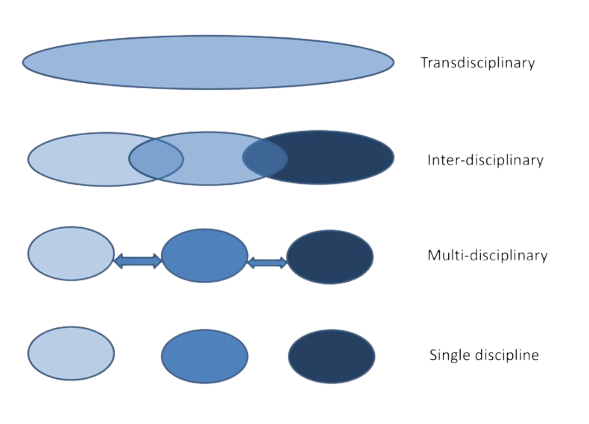

The transdisciplinary model of practice aims to provide more family-centred (Bruder, 2000), coordinated, and integrated services to meet the needs of children with complex learning needs and their families.

Our transdisciplinary work seeks to develop holistic provisions through working in a collaborative and integrated way, involving the perspective of people from different disciplines and those with lived experiences such as the child and their family. The transdisciplinary team thereby creates new ways to understand problems for the purposes of developing more effective solutions to meeting an individuals support needs as a whole. This differs from a multidisciplinary team, in which members use their individual expertise to first develop their own answers to a given issue, and then come together afterwards. (Bruder, 2000)

Our transdisciplinary work seeks to develop holistic provisions through working in a collaborative and integrated way, involving the perspective of people from different disciplines and those with lived experiences such as the child and their family. The transdisciplinary team thereby creates new ways to understand problems for the purposes of developing more effective solutions to meeting an individuals support needs as a whole. This differs from a multidisciplinary team, in which members use their individual expertise to first develop their own answers to a given issue, and then come together afterwards. (Bruder, 2000)

Transdisciplinary working has been long recognised as best practice for interventions in health care (Bruder, 2000) and they are now becoming more commonly used in specialist education settings (Roncaglia 2021). There is evidence that working in a transdisciplinary way also:

- Reduces fragmentation of service delivery/provision;

- Reduces confusion (and conflicts) in reports and communication with families;

- Promotes cooperation and coordination of the services offered to the child and their family.

(Carpenter, 2005; Davies, 2007)

Transdisciplinary teams work seamlessly together, sharing the teams‘ skills. Goals are aligned for better short and long-term positive outcomes. The benefits include :

- Team members around the child use strategies and approaches from all different disciplines;

- Team members develop greater awareness and understanding of different disciplines through sharing of information and best practice;

- Team members learn theories and methods from different disciplines;

- Team members learn to use all the above to embed the recommendations from different disciplines into the support for the child.

(King et al. 2009)

At Sherwood Foundation School the use of this model ensures that the people around the child/young person share skills, use consistent approaches and are equipped to effectively deliver the universal, targeted and specialist interventions offered. This also ensures the views and work of all disciplines, including those of the child/young person and their families, are fully considered and embedded within the curriculum and day to day running of the school. This model of working enables specialist teaching, wellbeing and therapeutic interventions to be moved effectively to targeted and universal options in order that the team around the child can better support the individual. This also ensures continuous growth of the whole school community through sharing of knowledge, enabling us to adapt alongside emerging and existing best-practice developments, as well as the lived experience of those using the service.

References & Useful Websites:

Carpenter, B. (2005). Real prospects for early childhood intervention: Family aspirations and professional implications. In B. Carpenter & J. Egerton (Eds.), Early childhood intervention. International perspectives, national initiatives and regional practice. Conventry, UK: West Midlands SEN Regional Partnership.

Davies, S. (Ed.). (2007). Team around the child: Working together in early childhood education. Wagga Wagga, New South Wales, Australia: Kurrajong Early Intervention Service.

Roncaglia, I. (2021). Using a Transdisciplinary approach to improve wellbeing. Published online by the National Autistic Society

https://www.autism.org.uk/advice-and-guidance/professional-practice/transdisciplinary-teams

https://citl.news.niu.edu/2020/11/17/transdisciplinary-interdisciplinary/

https://www.totalcommunication.com.sg/post/transdisciplinary-approach-what-does-it-mean

Our LEARN values

All staff at Sherwood Foundation School are supported to work within our LEARN values which embodies our mission and ethos to ensure best practice is achieved within our school every day:

Listening and responding to the voices of everyone in our community and beyond

Enabling our learners and the whole school community to be the best they can be

Accepting and celebrating individual differences and neurodiversity

Respecting our community in all areas of their lives & learning

Nurturing the individual to develop autonomy and independence

LEARNing happens everywhere at Sherwood Foundation School.

We are dedicated to using the following practices linked to our ethos and values and in order to best support the learning and growth of our pupils. We aim to create a school culture and learning environment that facilitates the active engagement and participation of our learners, using motivating and meaningful activities that support the development of regulation, communication, social communication, cognitive abilities and life skills in preparation for adulthood.

Strengths based and person-centred practice

Staff at Sherwood Foundation School recognise all the positive traits of our learners, including those related to their neurodiversity and/or disability that make them unique. This helps our learners and their families see that these traits positively contribute to their identity and to society. A strengths-based, person centred approach means focusing on what the person can do, not what they cannot do because of their neurodiversity or disability. There is a growing body of research to support the use of the strength-based approach in response to the growing understanding of the limitations associated with the deficit-based model of practice. The strength based approach encourages educators to:

- Understand that children’s learning is dynamic, complex and holistic;

- Understand that children and young people demonstrate their learning in different ways;

- Start with what’s present—not what’s absent—and further develop what works for the child/young person.

The underlying principles of the strength-based approach include:

- All children and young people have strengths and abilities;

- Children and young people grow and develop from their strengths and abilities;

- The problem is the problem—the child/young person is not the problem;

- When children/young people and those around them (including educators) appreciate and understand the individual child’s strengths, then the child/young person is better able to learn and develop.

- Neurodiversity and disability contributes to a diverse society.

Strengths can be defined as a child or young person’s intellectual, physical and interpersonal skills, capacities, dispositions, interests and motivations. When using a strength-based approach we question what works for the child, how it works and why so that those strategies can be continued and developed to match the child/young person’s abilities. The strength-based approach assists people (children, families and educators) to build a picture of what a child/young person’s learning and development can look like in the future. When using strength based practice there is a focus on the individual learner, taking a holistic and co-production approach, keeping the child/young person at the centre of all decisions, identifying what matters to them and how best outcomes can be achieved.

At Sherwood Foundation School we work collaboratively with our children and their families to identify the best next- steps for them, utilising all the strengths and resources they currently have or may have access to. This supports them in making autonomous and independent decisions about how they live and learn. Working in this way ensures that, as educators and practitioners, we are providing the right help, advice, and support at the right time, in the right place. This also ensures that we listen to the voices of autistic individuals and those with severe and profound learning difficulties and recognise that they are the real experts on autism and learning difficulties. We are committed to continually updating our beliefs as we listen, learn, and grow. At Sherwood Foundation School we believe that there are no limits on learning.

References & Useful Websites:

Carter, J. (2021). SEND Assessment: A Strengths-Based Framework for Learners with SEND. Routledge.

Department of Education and Early Childhood Development and Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority (2012). Strengths-Based Approach - A Guide to Writing Transition, Learning and Development Statements. Melbourne: State Government of Victoria, DEECD Publishing. Also published on https://www.education.vic.gov.au/documents/childhood/professionals/learning/strengthbappr.pdf

Green, B. L., McAllister, C. I., & Tarte, J. M. (2004). The strengths-based practices inventory: A tool for measuring strengths-based service delivery in early childhood and family support programs. Families in Society, 85(3), 327–334.

Lawrence-Lightfoot. S. (2003). The Essential Conversation. What Parents and Teachers can Learn From Each Other. Ballantine Books. New York.

McCashen, W. (2005). The Strengths Approach: A Strengths-based Resource for Sharing Power and Creating Change. Bendigo, Victoria: St. Luke’s Innovative Resources.

Siraj-Blatchford, I. (2009) Conceptualising progression in the pedagogy of play and sustained shared thinking in early childhood education: A Vygotskian perspective. Educational and Child Psychology, 26, (2), 77-89.

Using a Strengths-Based Therapeutic Approach with People with Developmental Disabilities https://www.mhddcenter.org/using-a-strengths-based-therapeutic-approach-with-people-with-developmental-disabilities/

Autistic strength focused podcasts and blogs https://learnplaythrive.com/podcast/

Care Act guidance on strengths-based approaches (2015) https://www.scie.org.uk/strengths-based-approaches/guidance

Thaking a strength based approach in our schools - TED talk (2018) https://www.onwardthebook.com/taking-a-strengths-based-approach-in-our-schools/

Relationship focused practice

The relationships in a child or young person’s life are very important to their wellbeing and development. In a school setting this means that their relationships with school staff, and with each other should be nurtured and supported. Relationship focused practice prioritises loving, caring relationships between practitioners and children and their families in order to help secure children’s well-being, improve behaviour and lead to more successful learning.

The relationships in a child or young person’s life are very important to their wellbeing and development. In a school setting this means that their relationships with school staff, and with each other should be nurtured and supported. Relationship focused practice prioritises loving, caring relationships between practitioners and children and their families in order to help secure children’s well-being, improve behaviour and lead to more successful learning.

Relationship focused approaches are those that emphasise connection, belonging and the teaching of effective self-regulation skills. These approaches assume that behaviour is a means of communication and that behaviour that is challenging to adults is actually stress behaviour and is generally a sign of unmet needs or that skills are needed that the child/young person has not developed yet. Relational approaches investigate behaviour and wellbeing issues with curiosity rather than judgement. They are grounded in psychological theory and support children to build their self-regulation skills through consistent co-regulation. They take into account the context and the child or young person's lived experiences and focus on the skills the child or those surrounding them need to learn to respond differently.

At Sherwood Foundation School we understand that, as humans, we develop through connected relationships based on feelings of safety, compassion, empathy and shared joy. We use relational focused interventions as a way of communicating, resolving difficulties, and building and strengthening the developmental relationships that are essential for effective learning. This ensures that our learners and their families feel that they belong to, and are a valued part of our school community and that their relationships with the adults in the school are positive, consistent, and based on trust and mutual respect. We also use this approach to build robust relationships with our stakeholders and outside agencies to ensure we can most effectively meet the complex needs of our learners and their families.

‘Staff forge strong and trusting relationships with pupils based on an acute understanding of their individual needs. This supports pupils to develop their self-regulation skills and their independence particularly well’ Ofsted 2024.

References & Useful Websites:

Carter, C.S. and Porges, S.W. (2013). ‘The biochemistry of love: an oxytocin hypothesis’. Science & Society, EMBO Reports, Vol. 14, Issue. 1: pp.12-16. Also published online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/embor.2012.191

Carter, C.S. (2017). ‘Oxytocin and human evolution’. In: Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp. 1-29. Also published online at https://doi.org/10.1007/7854_2017_18

Henderson, N. and Smith, H. (2022). Relationship-Based Pedagogy in Primary Schools - Learning with Love. Routledge.

Lilus, C., & Turnbull, J. (2009). Infant/Child Mental Health, Early Interventions and Relationship Based Therapies: A Neuro-relational Framework for Interdisciplinary Practice. W.W. Norton. New York.

Mahoney, G. and Perales, F. (2008). How relationship focused intervention promotes developmental learning. Down Syndrome Research and Practice online.

Mahoney, G. and Perales, F. (2003). Using Relationship-Focused Interventions to Enhance the Social Emotional Functioning of Young Children with Autistic Spectrum Disorder. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. Vol, 23 (2) pp.74-86. Also published online at

https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/02711214030230020301

NICE guideline [NG223] (2022). Social, emotional and mental wellbeing in primary and secondary education. Published: 06 July 2022. Available online. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng223/chapter/recommendations#whole-school-approach-2

Porges, S. (2011). The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. Norton.

Restall, G. J. and Eaan, M. Y. (2021) Collaborative relationship- focused Occupational Therapy: Evolving Lexicon and Practice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, Vol 88 (3) pp.220-230. Also published online at https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/00084174211022889

Rita Pierson - Every Kid Needs a Champion - TED Talk (2013)

https://www.ted.com/talks/rita_pierson_every_kid_needs_a_champion?language=en

The Polyvagal theory : The new Science of Safety & Trauma - TED Talk The Polyvagal Theory: The New Science of Safety and Trauma

What is Relationship Based Practice

https://www.education.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/1777612/Relationship-based-practice.pdf

Relationships & Belonging

Gaigg et al. (2018) An Evidence Based Guide to Anxiety in Autism. The Autism Research group.

https://www.city.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/466039/Anxiety-in-Autism-A5-guide.pdf

https://www.headstartkernow.org.uk/sec-sch-support/universal-/relationships/

Developmentally appropriate interventions

Developmentally appropriate practice is a way of teaching and delivering therapy that meets the needs of children and young people. It is a way of ensuring that goals and experiences are suited to the learning and development of the child/young person, are achievable and challenging enough to promote their progress and interest. This is particularly important for children with severe and/or profound learning difficulties, including those who additionally are autistic. The research for this approach is based on the principles in human development and learning. Those principles, along with evidence about curriculum and teaching/ therapeutic effectiveness, form a solid basis for decision making.

At Sherwood Foundation School, the transdisciplinary team use developmentally appropriate practices, informed by three core components, supporting them to make good decisions about the curriculum delivery and the use of individualised approaches, strategies and interventions for learners:

- Child development appropriateness - knowledge about the milestones and sequences of development, including how autistic children and young people and those with learning difficulties learn differently.

- Individual appropriateness - knowledge about the individual child or young person’s unique strengths, abilities, individual differences, interests, temperament, and approaches / barriers to learning.

- Social & cultural appropriateness - knowledge about each child or young person’s cultural and family background – his/her unique family, values, language, lifestyles, and beliefs.

References & Useful Websites:

Copple, C. & Bredekamp, S, (eds). (2009). Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Programs: Serving Children from Birth through Age 8, 3rd Edition. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

National Association for the education of young children. (2020) Developmentally Appropriate Practice. Published online at https://www.naeyc.org/sites/default/files/globally-shared/downloads/PDFs/resources/position-statements/dap-statement_0.pdf

Penn State University. Exploring developmentally appropriate practice. Published online at https://extension.psu.edu/programs/betterkidcare/early-care/tip-pages/all/exploring-developmentally-appropriate-practice

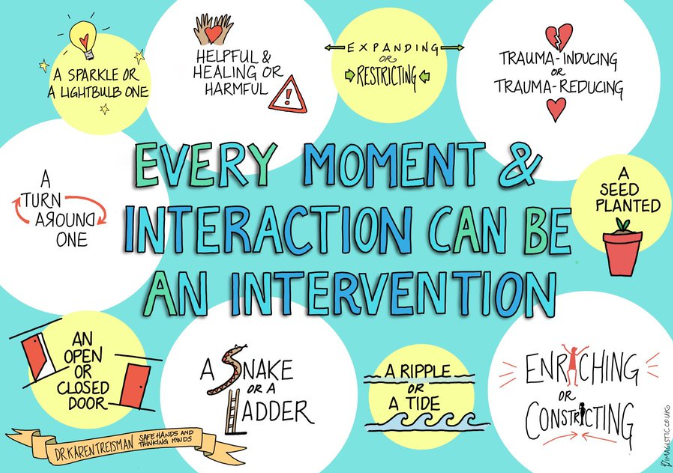

Trauma informed and applied practice

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are highly stressful & potentially traumatic events or situations that occur during childhood or adolescence. Traumatic events include maltreatment (abuse or neglect), violence & coercion (domestic abuse), adjustment (migration, asylum, ending of close relationships), prejudice (sexism, racism, ableism, LGBT+ prejudice), household or family adversity (substance misuse, intergenerational trauma, destitution, deprivation), inhumane treatment (imprisonment, institutionalisation), bereavement & survivorship (traumatic death, surviving illness or accident, living & coping with disability) (Bush, M. 2018).

ACEs have an impact on:

- A child’s development;

- Their relationships with others;

- Outcomes - ACEs increase the risk of the child/young person engaging in health harming behaviours & experiencing poorer mental & physical health outcomes in adulthood;

- Behaviour - A disproportionately high number of children/young people who show challenging behaviour have been exposed to trauma (CMH, 2020).

Around half of all adults living in Britain have experienced at least one form of adversity and 9% have experienced over 4 ACEs.

Trauma-informed practice is an approach to health, care and educational interventions which is grounded in the understanding that exposure to trauma can impact an individual’s neurological, biological, psychological and social development. The guidance covers the six principles of trauma-informed practice: safety, trust, choice, collaboration, empowerment and cultural consideration (DfE November 2022).

Trauma-informed practice is a whole-system approach where practitioners working with children:

- Realise what trauma is and how it can affect people and groups;

- Recognise the signs of trauma;

- Have systems in place that can respond to trauma;

- Support in resisting re-traumatisation.

A trauma informed school is one that is able to support children and young people who suffer with trauma or mental health problems and whose troubled behaviour acts as a barrier to learning. The wider goal is to minimise harm and promote wellbeing. Trauma informed schools UK state that this involves:

- Teaching young people about mental and physical well-being, often through relational and regulation focused approaches;

- Providing young people with a direct experience of reliable attachment figures;

- In a safe, caring environment.

At Sherwood Foundation School we take great pride in our school's offer which centres around the positive safeguarding, well-being and regulation of our whole school community. We also respect the differences of neurodivergent people and those with disabilities, whilst acknowledging the barriers they face to thriving in a world designed for neurotypical, physically able individuals. We do not use practices that promote masking or violate the bodily autonomy of our learners unless clearly specified in the learners positive handling plan. We are working well towards becoming a restraint free, trauma informed school (see our well-being policies).

References & Useful Websites:

ed. Bush, M. (2018). Addressing Adversity. Prioritising Adversity and Trauma-Informed Care for Children and Young People In England. Young Minds. NHS Health Education England.

Baumeister, R. E. & Vohs, K. D. (Eds). (2011) Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory and Applications (2nd ed). Guildford Press. New York

Beacon House: Schools resource list https://beaconhouse.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Schools-Resources-List-2022.pdf

Beacon House - Trauma informed training & resources - https://beaconhouse.org.uk/resources/

Beacon House - Training https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Apl_IB_rDKk

Ford, T et al (2021) Mental Health of Children and Young People During the Pandemic, British Medical Journal; 372 doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n614 Cite this as: BMJ 2021;372:n614

NICE guideline [NG223] (2022). Social, emotional and mental wellbeing in primary and secondary education. Published: 06 July 2022. Available online. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng223/chapter/recommendations#whole-school-approach-2

Perry, B & Winfrey, O. (2020). What Happened To You? Conversations on Trauma, Resilience and Healing

Porges, S. W. (2017) The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory: The Transformative Power of Feeling Safe. W.W Norton & Company.

Shanker, S. (2016). How to Help your Child (and You) Break the Stress Cycle and Successfully Engage in Life. Penguin Press. London.

Trauma informed Schools UK - https://www.traumainformedschools.co.uk/ ;

Wilton. J (2020) Briefing 54: Trauma, challenging behaviour and restrictive interventions in schools https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/trauma-challenging-behaviour-and-restrictive-interventions-schools

Saxton, J. (2019) Trauma-informed schools: How Texas schools and policymakers can improve student learning and behaviour by understanding the brain science of childhood trauma. Texans Care for Children [Online] Available at: https://txchildren.org/posts/2019/4/3/traumainformed-schools

van der Kolk, B (2014). The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma. Penguin Publishing. London. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QSCXyYuT2rE

YoungMinds (2017) Wise up: Prioritising wellbeing in schools. YoungMinds [Online] Available at: https://youngminds.org.uk/ media/1428/wise-up-prioritising-wellbeing-inschools.pdf

Young Minds - Trauma informed schools - https://www.youngminds.org.uk/media/hvsd11j0/trauma-informed-schools.pdf

DfE, November 2022

Neuroscience aligned practice

The brain mediates our thoughts, feelings, actions and connections to others and the world. Now, more than ever before, we understand the core principles of neuroscience, including neuroplasticity and neurodevelopment and this can help us better understand ourselves and others. The research from the fields of neuroscience, physiology, psychophysiology, psychology and clinical practice are continuously being used to:

- Increase our understanding of the “why” of a child’s behaviour and;

- Help us to determine “how” best to support the child in all aspects of their life and learning

At Sherwood Foundation School we attempt to ensure that, where possible, our approaches are aligned with current evidence from neuroscience and combined with the views and lived experience of people with learning difficulties, autistic individuals and those with neuro-developmental disorders. This ensures that we are building a bridge between neuroscience and practice, to work together with all agencies to develop better, more effective and evidence-based models of preventative support and interventions for the children & young people attending our school.

References & Useful Websites:

Delahooke, M. (2019). Beyond Behaviours. Using Brain Science and Compassion to Understand and Solve Children’s behavioural Challenges. John Murray Press. London.

Feldman-Barrett, L. (2017). How Emotions Are Made. The Secret Life of the Brain. Pan MacMillan. U.K.

MacLean, P. D. (1990). The Triune Brain in Evolution: Role in Paleocerebral functions. New York, NY: Plenum.

O’Hearn, K., Asato, M., Ordaz, S. & Luna B. (1998). Neurodevelopment and executive function in autism. Developmental Psychology. 20(4):1103-32.

Perry, B & Winfrey, O. (2020).. What Happened To You? Conversations on Trauma, Resilience and Healing

Porges, S. W. (2017) The Pocket Guide to the Polyvagal Theory: The Transformative Power of Feeling Safe. W.W Norton & Company.

Sameroff, A. (2010) A Unified Theory of Development: A Dialectic Integration of Nature and Nurture. Child Development 81 (1) p 6-22

Siegal, D & Bryson, T. P (2011). The Whole Brain Child. Random House. New York.

Shanker, S. (2016). Help your Child Deal with Stress and Thrive – The Transformative Power of Self-Reg. Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. London.

Shanker, S. (2016). How to Help your Child (and You) Break the Stress Cycle and Successfully Engage in Life. Penguin Press. London.

Theyer, R. E. (1996). The Origin of Everyday Moods: Managing Energy, Tension and Stress. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press

Bruce Perry - Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TpsK_fY2BpQ

NSPCC - Accessible Neuroscience https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/news/2020/september/making-neuroscience-more-accessible

Neurodiversity Affirming Practice

We wholeheartedly embrace the concept of the neurodiversity paradigm, recognising that neurological differences, including autism, are natural variations in the human experience. We respect and value the diverse perspectives and strengths that neurodivergent individuals bring to our school. Our school is committed to creating an inclusive environment where all participants can engage in meaningful activities, and learn in a way that works for them. We adapt our practices and approaches to accommodate the unique needs and preferences of our pupils, their families and staff. We actively normalise diversity in all its forms throughout the school, at all levels, taking opportunities as they arise to reinforce messages of acceptance.

-

Whole school approaches

- Process-based, quality first teaching and learning delivered through the tiered model

- Well-being and regulation approaches underpinned by the practice of Self-Reg

- Low Arousal Approach & Studio 111

- Sensory & Physical Supports

- Relationship and play focused approaches rooted in the DIR- Philosophy

- Attention & Engagement (Engagement Model, Curiosity Approach & Attention Autism)

- Total communication approach, including use of aided language stimulation & robust AAC

- Natural Language Acquisition and Gestalt Language Processing

- Transactional Supports

- Developing independence

- Environmental adaptations and assistive technology

- Parent co-production, coaching & support

Process-based, quality first teaching and learning delivered through the tiered model

Process based learning is a holistic approach where the process of teaching becomes the objective because it encourages the teacher to structure planning around an open-ended philosophy. The entire process of learning is taken as a whole, as opposed to teaching to specific individualised targets. The assumption of process based teaching provides a platform for varied and disparate learning to take place, and individual progression may only be recognised in retrospect, at the end of each session, week, half--term, term and/or year. This retrospective target setting is particularly used to reduce the tendency of objectives or target based teaching to narrow the learning opportunities offered to those with PMLD and SLD.

Quality First Teaching (QFT) is a whole school teaching concept that focuses on high quality and inclusive teaching for every child in a classroom. QFT relies on a variety of learning methods in order to be effective, like differentiated learning and the use of a range of approaches and resources appropriate for the cohort. QFT is an approach that highlights the need for a personalised learning experience and encourages greater understanding of the specialist SEND needs of our learners.

Whilst all of the pupils at our school require specialist approaches to enable effective and accessible learning, at Sherwood Foundation School we continue to use process based, quality first teaching and learning following the three-tiered model (explained below) in order to gain the best outcomes for our learners. We have individualised this model for use by our trans-disciplinary team to provide a framework, to make the learning more accessible and inclusive for our learners, as well to ensure we are enriching learning outcomes and further upskilling our transdisciplinary team:

Universal Level - ‘All means All’

This first step is simply Quality First Teaching. At the universal level teachers are encouraged to plan each lesson using a range of trans-disciplinary approaches, and pedagogical choices so that there are clear learning objectives to help them meet the learning outcomes for all learners. The focus is scratch and challenge throughout all aspects of learning.

Targeted Level - Additional Interventions

Trans-disciplinary targeted interventions are used alongside our universal offer in order to provide extra support to pupils, often delivering interventions supported by specialist teachers, therapists or well-being practitioners. This extra support is generally fully integrated in lessons and is how highly differentiated activities and interventions are used to great effect.

Specialist Level - Highly Personalised Interventions

Specialist level interventions are delivered by teachers, highly skilled teaching assistants and members of the trans-disciplinary team either directly or overseen by those with high levels of specialist knowledge. Where possible these interventions are provided within class learning with a whole class group, a group of learners and individually, embedded into the curriculum and teaching wherever possible.

How Efficacy is Ensured through Training of Staff

Monitoring of quality first teaching is overseen by the Heads of School on each campus. They are responsible for ensuring the quality of teaching and learning and for monitoring the impact of this in relation to outcomes and destinations. The school appraisal system, coaching and support for teaching staff, alongside our CPD strategy ensures quality in this area is maintained. The quality of the pastoral support offer is overseen by the Head of Strategy and Pastoral Support in collaboration with the Heads of School

References & Useful Websites:

Coe, R. and Aloisi, C. and Higgins, S. and Major, L.E.(2014) ‘What makes great teaching? Review of the underpinning research.’, Project Report. Sutton Trust, London.

Department of Education (2015) Special educational needs and disability code of practice: 0 to 25 years Statutory guidance for organisations which work with and support children and young people who have special educational needs or disabilities. Published online at:

Department for Education and Skills (2007). Pedagogy and Personalisation. London: Department for Education and Skills.

Department for Children, Schools and Families (2007). Pedagogy and Personalisation. London: Department for Education and Skills. Accessed online at:

Imray, P. (2010). A PMLD Curriculum for the 21st Century. Published online at:

Imray, P. (2021) A Different View of Literacy.

Imray, P. & Hinchcliffe, V. (2013). Curricula for Teaching Children and Young People with Severe or Profound and Multiple Learning Difficulties: Practical strategies for educational professionals. Nasen spotlight.

Quality First Teaching - Information video -

Wellbeing and regulation approaches underpinned by the practice of Self-Reg

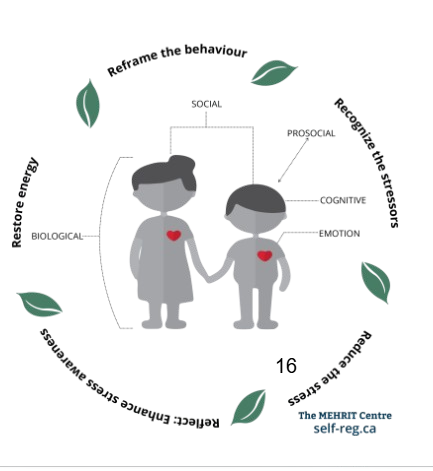

Shanker Self-Reg - A Process for Calm Alert Learning

Self-Reg (Shanker 2012, 2016, 2016, 2019, 2020) is a process for enhancing self-regulation by understanding stress and managing energy and tension. It is an ongoing lifelong process not a program that is based on a large body of scientific research. The process of Self-Reg is used by school leaders to provide:

Self-Reg (Shanker 2012, 2016, 2016, 2019, 2020) is a process for enhancing self-regulation by understanding stress and managing energy and tension. It is an ongoing lifelong process not a program that is based on a large body of scientific research. The process of Self-Reg is used by school leaders to provide:

- A vision is for calm, alert children, youth and adults flourishing in physically and emotionally nurturing environments

- A whole systems approach to learning and living in self-regulation.

Through the practice of Self-Reg, we learn how to:

- Reframe behaviour, our own as well as another’s;

- Recognise stressors – both overt and hidden;

- Acquire strategies to reduce the stress;

- Reflect and become aware of what it feels like to be calm and what it feels like to be over-stressed; and finally,

- Develop restorative practices that enhance our capacity, not to cope with, but rather to thrive on the various stresses that are abound in modern life.

(Shanker, S. & Hopkins, S. 2019)

Our Mission at Sherwood Foundation School is to provide a strengths based, wellbeing centred education, rooted in Self-Reg. The practice of Self-Reg is therefore central to our teaching, wellbeing and therapeutic universal offer, overlapping with and supporting our LEARN values. It is used at all levels of school life from informing our curriculum to forming the basis for how we coach staff in how they communicate with and respond to others. Many of the interventions delivered at targeted & specialist level are delivered through a Self Reg (and Co-Reg) lens. We are passionate about being a Self-Reg Haven school.

‘Pupils learn how to self-regulate or seek the support of staff when they cannot do this on their own. This has led to a significant improvement in behaviour’ Ofsted 2024

How Efficacy is Ensured through Training of Staff

The practice of Self-Reg is overseen by our Head of Strategy & Pastoral Support who has training in Self-Reg at Leadership & Facilitator level and attends regular conferences and training updates. All teachers, well-being practitioners and therapists have been offered training at 101 level and in depth whole school training has meant that the team is working hard to embed the practice of Self-Reg into everyday school life. All of our staff are given training during their induction on this approach and all teaching and therapy staff receive regular Self-Reg training updates. The school approach to coaching and supporting our teaching staff and therapists, alongside our CPD strategy ensures we continue to develop and grow our practice in this area.

References & Useful Websites:

Shanker, S. (2016). Help your Child Deal with Stress and Thrive – The Transformative Power of Self-Reg. Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. London.

Shanker, S. (2016). How to Help your Child (and You) Break the Stress Cycle and Successfully Engage in Life. Penguin Press. London.

Shanker, S. & Hopkins, S. (2019). Self-Reg Schools: A Handbook for Educators. Toronto Press. London.

Shanker, S. (2020). Reframed – Self-Reg for a Just Society. Toronto Press. London.

YoungMinds (2017) Wise up: Prioritising wellbeing in schools. YoungMinds [Online] Available at: https://youngminds.org.uk/ media/1428/wise-up-prioritising-wellbeing-inschools.pdf

Sel-Reg - Official website -

What is Self-Reg -

What is a Self-Reg Haven -

Baumeister, R. E. & Vohs, K. D. (Eds). (2011) Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory and Applications (2nd ed). Guildford Press. New York

Dijkhuis, R. et al. (2017). Self-regulation and quality of life in high-functioning young adults with autism. Autism, 21(7), 896–906. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361316655525

Eisenberg, N. et al (2003). Longitudinal relations among parental emotional expressivity, children’s regulation, and quality of socioemotional functioning. Developmental Psychology, 39(1), 3–19. https://doi. org/10.1037/0012-1649.39.1.3

Feldman-Barrett, L. (2017). How Emotions Are Made. The Secret Life of the Brain. Pan MacMillan. U.K.

Fredrickson & Joner (2002). Positive Emotions Trigger Upward Spirals Toward Emotional Well-Being Psychological Science

Gillott, A., & Standen, P. J. (2007). Levels of anxiety and sources of stress in adults with autism. Journal of intellectual disabilities, 11(4), 359–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629507083585

Gulsrud, A. C., Jahromi, L. B., & Kasari, C. (2010). The co-regulation of emotions between mothers and their children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 40(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-009-0861-x

Jahromi, L. B et al (2012). Emotion regulation in the context of frustration in children with high functioning autism and their typical peers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 53(12), 1250–1258. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02560.x

Kopp, C. B. (1982). Antecedents of self-regulation: A developmental perspective. Developmental Psychology, 18(2), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.18.2.199

Mazefsky, C. A. (2015). Emotion regulation and emotional distress in autism spectrum disorder: Foundations and considerations for future research. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(11), 3405–3408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-015-2602-7

Pauen, S. (2016) Understanding early development of self-regulation and co-regulation: EDOS and PROSECO. Psychology emanticscholar.org/paper/Understanding-early-development-of-self-regulation-Pauen/b08eb6fcb51c7d4d35a11e22bb6bc892f61b17fb

Sameroff, A. (2010) A Unified Theory of Development: A Dialectic Integration of Nature and Nurture. Child Development 81 (1) p 6-22

Shanker, S. (2012). Calm, Alert, and Learning – Classroom Strategies for Self-Regulation. Pearson. Canada.

Sameroff, A. J., & Fiese, B. H. (1990). Transactional regulation and early intervention. In S. J. Meisels & J. P. Shonkoff (Eds.), Handbook of early childhood intervention (pp. 119–149). Cambridge University Press.

Low Arousal Approach & Studio 111

The Low Arousal approach emphasises a range of behaviour management strategies that focus on the reduction of stress, fear and frustration It seeks to prevent aggression and crisis situations through creating a caring environment characterised by calm and positive expectations aiming to decrease stress and behaviour that challenges.

The core values of a low arousal approach are:

- A non-confrontational way of recognising and managing signs of stress/behaviours of concern

- A philosophy of care which is based on valuing people

- An approach that specifically attempts to avoid aversive interventions

- An approach that requires staff to focus on their own responses & behaviour & not just locate the problem in the person with the label

Studio 111 is the provider the school uses to support our staff to manage distress and challenging behaviours when they arise. We use this alongside our LEARN values and the process of Self-Reg as a way of supporting our staff to understand and manage stress in themselves and in the pupils they support.

Studio 3 strongly aligns with our vision that our pupils need relationship focused approaches, founded in understanding stress and regulation as an alternative to restrictive interventions for managing and controlling behaviour. Studio 111 are strongly anti-restraint and never advocate the use of restrictive practices in care and school environments. Whilst they sometimes teach gentle physical skills on a case-by-case basis, they never teach restraint holds and do not sanction seclusion of any kind. We are committed to being a restraint free school and are transparent about any use of restrictive practice.

The Studio 111 Low Arousal Approach, embedded within the process of Self-Reg, enables professionals, carers and family members at Sherwood Foundation School to support and manage distressed and challenging behaviours when they arise. It equips them with the tools to create systems of support around individuals to manage stress and trauma. The approach empowers the individual or team to focus on the ‘person’ in the situation, identify causes for distressed behaviour, and use proven Low Arousal skills to reduce distress and improve overall well-being. The low arousal approach, like Self-Reg, acknowledges that stress is an ever present part of all our lives and asks how we can best manage crisis situations and where and how we can best support these as practitioners.

‘Pupils’ welfare, care and safety are at the centre of everything that staff do’. Ofsted 24.

How Efficacy is Ensured through Training of Staff

Sherwood Foundation School has Studio 111 trainers within our teaching and wellbeing team to ensure we can effectively train and support our staff and parents/carers. Our Lead Wellbeing Practitioner meets regularly with the Studio 111 team and ensures our trainers keep up to date with changes in practice. All teaching staff, leaders, wellbeing practitioners and therapists are trained in this approach and have annual updates. This is supported by Wellbeing (Behaviour) Policy and our Restrictive Practice Policy.

References & Useful Websites:

The Low Arousal Approach

ed. Bush, M. (2018). Addressing Adversity. Prioritising Adversity and Trauma-Informed Care for Children and Young People In England. Young Minds. NHS Health Education England.

Baumeister, R. E. & Vohs, K. D. (Eds). (2011) Handbook of Self-Regulation: Research, Theory and Applications (2nd ed). Guildford Press. New York

BILD (2016) The seven key questions about Positive Behaviour Support. NHS England [Online] Available at: https://www. england.nhs.uk/6cs/wp-content/uploads/ sites/25/2016/07/bild-key-questions.pdf.

Bundy, A. C. et al (2002) Sensory Integration Theory & Practice. F. A. Davis. Philadelphia.

Care Quality Commission (2020) Out of Sight: Who Cares? A review of restraint, seclusion and segregation for autistic people, and people with a learning disability and/or mental health condition. https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20201218_rssreview_report.pdf

CBF/PABSS (2019) Reducing restrictive intervention of children and young people. The Challenging Behaviour Foundation [Online] Available at: https://www.challengingbehaviour. org.uk/learning-disability-assets/ reducingrestrictiveinterventionof childrenandyoungpeoplereport.pdf.

Chlidren’s Society (2023) The Good Childhood Report https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-09/The%20Good%20Childhood%20Report%202023.pdf

schools Research report https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/65eee4ba3649a26deded6320/Reasonable_force__restraint_and_restrictive_practices_in_alternative_provision_and_special_schools.pdf

Department for Education (2019a) Permanent and fixed period exclusions in England: 2017 to 2018. Department for Education [Online] Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/820773/Permanent_and_fixed_period_exclusions_2017_ to_2018_-_main_text.pdf.

DfE (2019b) Timpson review of school exclusion: Technical note. Institute of Education [Online] Available at: https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/33359/4/ Technical_note.pdf.

Greene, R. (2014) Lost in School. Why our Kids with Behavioural Challenges are Falling Through the Cracks and How Can We Help Them. Scribner. New York

The ICARS report against Seclusion & Restraint in English Schools (2023) https://againstrestraint.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/icars_report_23.pdf

Kohn, A. (2006) (10th edn). Beyond Discipline. From Compliance to Community .ASCD Publications. USA

House of Commons Briefing: School exclusions (26 February 2020) Local Government Association https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cdp-2020-0032/

Jay, M (2021) Achievement Beyond IQ: Childhood Regulation. Reason Beyond Restraint https://reasonwithoutrestraint.com/achievement-beyond-iq-childhood-self-regulation/

McDonnell, A. (2024) Freedom from Restraint & Seclusion: The Studio 111 Approach

YoungMinds (2017) Wise up: Prioritising wellbeing in schools. YoungMinds [Online] Available at: https://youngminds.org.uk/ media/1428/wise-up-prioritising-wellbeing-inschools.pdf

Relationship and play focused approaches rooted in the DIR- Philosophy

DIR is a comprehensive framework for understanding human development and how each person individually perceives and interacts with the world differently. It is based on the Developmental Individual-difference Relationship-based model (DIR) developed by Dr. Stanley Greenspan. It outlines the critical role social-emotional development has on overall human development starting at birth and continuing throughout the lifespan. The model highlights the power of relationships and emotional connections to fuel development. Through a deep understanding of the "D" and the "I" we can use the "R" to promote healthy development and to help everyone reach their fullest potential. DIR® is rooted in the science of human development and is a pathway to promote healthy development in a respectful manner that builds connections, understanding, communication, and engagement.

At Sherwood Foundation School we believe that the principles of DIR can be used within ANY interaction, with anybody at ANY time across the day, and does not have to be a planned/structured session (as described in DIR Floortime - see interventions section). Staff use the DIR philosophy to understand a learners strengths, motivations, preferences and individual differences in order to support them to initiate and engage in spontaneous and purposeful interactions, cope with and manage big emotions, stay engaged with others for longer through back and forth interaction and circles of communication, and feeling secure and comfortable exploring things that might be hard for them.

How Efficacy is Ensured through Training of Staff

The DIR Philosophy is overseen by our Head of Strategy & Pastoral Support, who also has oversight of the Well-being and the Play & Leisure Curriculum Teams. She has training in DIR at 202 level and attends regular conferences and training updates. Some of our teachers and therapists have DIR training at 101, 201 and 202 level and are attached to the Play & Leisure or Wellbeing curriculum teams to ensure that DIR is embedded in our school offer and curriculum offer. All teaching, wellbeing and therapy staff have received basic training in DIR and the school approach to coaching and supporting our teaching staff and therapists, alongside our CPD strategy ensures we continue to develop and grow our practice in this area.

References & Useful Websites:

Affect Autism - Official Website

Cullaine. D. (2016). Behavioral Challenges in Children with Autism and Other Special Needs: The Developmental Approach. Norton & Company Limited. London.

Davis, A. et al. (2014). Floortime Strategies to Promote Development in Children and Teens. A Users Guide to the DIR Model Paul Brookes Publishing Co. U.S.

Delahooke, M. (2019). Beyond Behaviours. Using Brain Science and Compassion to Understand and Solve Children’s behavioural Challenges. John Murray Press. London

Devin M. et al (2013) Learning through interaction in children with autism: Preliminary data from a social-communication-based intervention Autism 2013 17: 220 originally published online 26 September 2011 DOI: 10.1177/1362361311422052. The online version of this article can be found at: http://aut.sagepub.com/content/17/2/220

DeGangi, G. (2000). Pediatric disorders of regulation in affect and behavior: A therapist’s guide to assessment and treatment. Academic Press.

DIR Official Website - https://www.icdl.com/dir

Greenspan, S., and Wieder, S. (1998). The Child with Special Needs: Encouraging Intellectual and Emotional Growth. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley

Greenspan, S., and Wieder, S. (2006). Engaging Autism: Using the Floortime Approach to Help Children Relate, Communicate, and Think. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley

Whitehouse, A et al (2020) Interventions for children on the autism spectrum: A synthesis of research evidence. autismcrc.com.au. Australian Government

Total communication approach, including use of aided language stimulation & robust AAC

Our goal at Sherwood Foundation School is for our learners to be autonomous communicators. This means “Being able to say what I want to say, to whoever I want to say it to, whenever I want to say it, however I choose to say it” (Gayle Porter, Speech Language Pathologist). In order to achieve this we use a total communication approach (or a total ‘toolbox’ approach). We acknowledge and accept all forms of communication as equally valued, whilst shaping it to become more conventional. This approach is also about finding and using the right combination of communication methods for each child/young person (for example which aided and unaided AAC is best for each learner). This approach supports an individual to form connections and have positive social experiences; which promotes successful interactions, and develops the skill of meaningful two way communication. This is achieved within meaningful, playful and natural interactions. Our staff understand that for a total communication approach to be effective, the following three components need to be included in the approach:

- Identifying, responding to and shaping the learner’s natural mode of communication.

- Motivating the learner by providing a meaningful reason for him/her/them to communicate.

- Creating an aided language learning environment (modelling AAC while speaking, for example using Makaton signs or pointing to symbols on a coreboard/PODD system while saying the word aloud). An effective communication partner achieves this by practising and creating many opportunities for the learner to communicate by:

- Following their lead

- Using affect (the use of facial expressions, gestures, body language, and tone of voice to express ideas and emotions)

- Acknowledging all natural communication attempts

- Attributing meaning (providing meaning to non-speaking communication attempts, for example if a child pushes away their plate of food, the adult says “I think you’re finished” alongside aided language input)

- Using aided language input on a learners AAC system

- Commenting on what the learner is seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, feeling and touching to teach new vocabulary

- Making a higher ratio of comments to questions (e.g. 4:1)

- Providing communication temptations and building anticipation

- Giving wait time

- Modelling language one step ahead of where the learner is at (zones of proximal development)

- Ensuring that all learners and staff have access to the learners respective AAC systems at all times

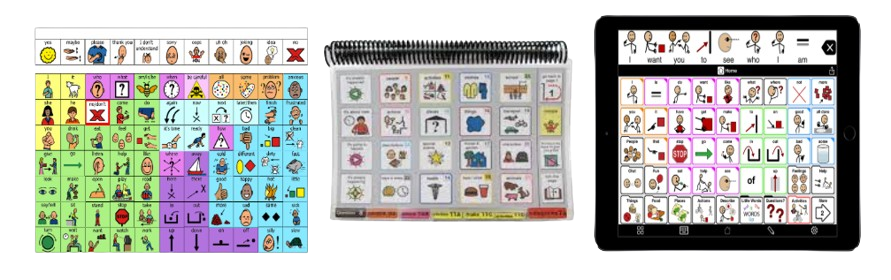

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) is anything that supplements or replaces spoken language. The following are the different categories of AAC and some examples within each (details to be found on our interventions page):

- Unaided (use of body) AAC - requires no additional materials other than a person’s body (e.g. gesture, facial expression, body language, Makaton, British Sign Language, TaSSeLS)

- No/low tech AAC (aided) - communication method that is not electronic but requires equipment outside of a person’s body (e.g. objects of reference, visual timetables, now/next board, paper based symbol systems - core vocabulary board, PODD book)

- Mid tech AAC (aided) - electronic devices that are (usually) battery-operated and have simpler functions (e.g. GoTalk, switches with pre-programmed messages such as a BigMac).

- High tech AAC (aided) - electronic devices with more advanced processors, most of which have voice output (e.g. communication devices - iPad with Proloquo2Go / LAMP / PODD app, eye gaze)

At Sherwood Foundation School we prioritise the use of aided AAC as it makes spoken language more permanent and predictable; it scaffolds and supports the learners’ understanding (receptive language); and it provides the learner with access to a range of methods to communicate in a way that can be understood by everyone (conventional expressive communication). Therefore, in order for the learner’s message to be understood, the listener (e.g. communication partner) does not need to be trained on aided AAC. This enables our learners to communicate with whomever they wish (i.e. in the community setting) and is an important step as they prepare for adulthood. We promote all areas of communication development in relation to AAC in order for our learners to achieve communication competence (operational, linguistic, social and strategic skill sets). Prompting is not advised as this does not promote spontaneous and natural communication; however a prompt hierarchy may be implemented with close supervision from the treating speech and language therapist. This is further assessed and supported at a targeted and specialist level.

Those who rely on AAC strategies begin as AAC novices and evolve in competence to become AAC experts with support, encouragement, role models, and teaching strategies. One of the ways to provide education and communication opportunities in using AAC is through Aided Language Input. Aided Language Input is actively using symbols alongside spoken language when speaking to an individual to show them how to use the AAC system to communicate with others.

‘Staff ably use a wide range of resources, such as objects of reference, signs, symbols and technology. This helps pupils who are non-verbal to communicate their wishes and to make choices and contributes to creating a school where every pupil has a voice.’ Ofsted 2024

How Efficacy is Ensured through Training of Staff

The practice of a Total Communication Approach, including the use of aided language input and AAC is overseen by our Head of Strategy & Pastoral Support as well as the Head of School responsible for the oversight of the Communication & Literacy Curriculum Team. Both senior leaders work closely with our lead speech and language therapists on each campus and the teaching and therapy staff within the communication and literacy curriculum team to ensure best practice is embedded within our whole school universal offer and curriculum delivery. All of our Senior Leaders have training in the use of AAC and look to our speech and language therapy leads for advice and best practice updates. All of our staff are given training during their induction on this approach and all teaching and therapy staff receive regular communication training updates and specialist training e.g. PODD, BSL. We have an allocated Makaton ‘champion’ on both campuses who supports the whole school with understanding and using Makaton throughout their day, through regular communication briefings. The school approach to coaching and supporting our teaching staff and therapists, alongside our CPD strategy ensures we continue to develop and grow our practice in this area.

References & Useful Websites:

Total communication approach: www.slt.co.uk/speech-language-and-communication/one-to-one-therapy/total-communication-approach/

Youtube video about aided language stimulation: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=psIiou_Hb1U

What is aided language stimulation: https://www.communicationcommunity.com/what-is-aided-language-stimulation/

Makaton: https://makaton.org/

Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists - information page about robust augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) systems https://www.rcslt.org/speech-and-language-therapy/clinical-information/augmentative-and-alternative-communication/

Janice Light & David McNaughton (2014) Communicative Competence for Individuals who require Augmentative and Alternative Communication: A New Definition for a New Era of Communication?, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 30:1, 1-18, DOI: 10.3109/07434618.2014.885080

Kristi L. Morin, Jennifer B. Ganz, Emily V. Gregori, Margaret J. Foster, Stephanie L. Gerow, Derya Genç-Tosun & Ee Rea Hong (2018) A systematic quality review of high-tech AAC interventions as an evidence-based practice, Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 34:2, 104-117, DOI: 10.1080/07434618.2018.1458900

Leonet O, Orcasitas-Vicandi M, Langarika-Rocafort A, Mondragon NI, Etxebarrieta GR. A Systematic Review of Augmentative and Alternative Communication Interventions for Children Aged From 0 to 6 Years. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2022 Jul 6;53(3):894-920. doi: 10.1044/2022_LSHSS-21-00191. Epub 2022 Jun 27. PMID: 35759607.

O'Neill T, Light J, Pope L. Effects of Interventions That Include Aided Augmentative and Alternative Communication Input on the Communication of Individuals With Complex Communication Needs: A Meta-Analysis. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2018 Jul 13;61(7):1743-1765. doi: 10.1044/2018_JSLHR-L-17-0132. PMID: 29931287.

Walker, V. L, & Snell, M. E (2013). The Effects of Augmentative and Alternative Communication on Challenging Behaviour: A Meta-analysis. Augmentative and alternative communication. 29 (2) 117-131

Whitehouse, A et al (2020) Interventions for children on the autism spectrum: A synthesis of research evidence. autismcrc.com.au. Australian Government

Natural Language Acquisition and Gestalt Language Processing

Previously, most children were thought to develop language in a linear manner whereby they start at single words and continue to build more complex phrases, onto sentences and so on. This is called analytic language development or analytic language processing (ALP). While some children do still learn this way, many autistic learners and some learners with complex communication profiles develop language through gestalt language processing (GLP). This is where children use delayed echolalia, or ‘chunks’ (units) of language initially to communicate, before ‘breaking’ (mitigating) the chunks into smaller pieces, beginning to create more flexible and novel phrases. These ‘chunks’ can vary in size; ranging from single words to entire songs or books. Over time, both ALP and GLP users have language which becomes more flexible and self-generated, they just follow a different path to get there. Not all GLP users have delays, or require language interventions to support their language acquisition however many of the learners at Sherwood Foundation School do.

The natural language acquisition protocol (NLP) (Blanc, 2012) identifies six stages of gestalt language development, with suggested strategies at each stage to support the progression of the stages. The underpinning theme across all stages of NLP is the development of trust and connection between the child or young person and their communication partner. This creates the feelings of safety and promotes meaningful and authentic communication opportunities. These strategies closely align with the strategies identified in DIR-Floortime and DIR-Philosophy and with Sherwood Foundation Schools values and school ethos.

The six stages of the NLP can be seen below (Blanc 2012):

|

Stage |

Description |

|

1 |

Language gestalts (whole, scripts, songs) |

|

2 |

Mitigations (mitigated gestalts or partial scripts) Mix and match stage |

|

3 |

Isolated single words Two-word combinations of single words |

|

4 |

Novel phrases and beginning of sentences |

|

5 |

Novel sentences with more complex sentences |

|

6 |

Novel sentences using a complete grammar system |

From stage 4, ALP strategies and approaches become appropriate. Students at Sherwood Foundation School who are gestalt language learners require a robust and specialist assessment and ongoing specialist tracking of language development in order to identify their language stage and the appropriate strategies. This intervention therefore sits within our targeted and specialist therapy offer and is most successful when family members/caregivers are involved in the delivery of the therapy in addition to teaching staff.

How Efficacy is Ensured through Training of Staff

The approach of the Natural Language Acquisition Protocol (NLP) for gestalt language processors is overseen by our Head of Strategy & Pastoral Support, as well as the Head of School responsible for the oversight of the Communication & Literacy Curriculum Team. Both Senior Leaders work closely with our lead speech and language therapists on each campus and the teaching, and therapy staff within the communication and literacy curriculum team to ensure best practice is embedded within our whole school universal offer and curriculum delivery. All speech and language therapists have attended an in person or virtual two-day course detailing GLP and the NLP. Our Senior Leaders have universal training on GLP and look to our speech and language therapy leads for advice and best practice updates. All education staff members have training on GLP as a part of our universal offer and are given annual training on updates in the field of autism best practice and therapeutic approaches in relation to GLP and NAP. The school approach to coaching and supporting our teaching staff therapists, alongside our CPD strategy ensures we continue to develop and grow our practice in this area.

References & Useful websites:

Blanc, M., Blackwell, A., & Elias, P. (2023). Using the Natural Language Acquisition protocol to support gestalt language development. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1044/2023_PERSP-23-00098

Blanc, M. (2012). Natural Language Acquisition on the autism spectrum: The journey from echolalia to self-generated language. Communication Development Center, Inc.

Meaningful Speech Website: https://www.meaningfulspeech.com/

Environmental adaptations and assistive technology

Sherwood Foundation School aims to utilise environmental adaptations and assistive technology wherever possible in order to promote independence and autonomy in our learners as well as to create wider opportunities for learning. Individuals with complex physical difficulties or sensory impairments (e.g. visual or hearing) may utilise environmental adaptations and assistive technology to support their independence and to access education, leisure and functional activities. They therefore need to establish their access points (e.g. head, elbow, hands or feet) on their body to support them to control their environment through use of alternative access equipment (e.g a variety of switches, joysticks, trackpads, eye gaze technology, adapted keyboards and mice etc). Accessible devices such as ‘adaptive switches’ or joysticks, allow learners to perform complex actions, such as to operate a toy, control volume of music, change the television channel, turn the lights on or off, participate in a computer game or operate a mobility aid such as a power chair. A switch can also be used by those with communication needs as a medium of communication (e.g. voice output Big MAC switch, switch adapted high tech AAC system). Adapted keyboards (e.g. enlarged keys, colour coded letters etc) and mice (e.g. Trackball or Orbitrack) can also be used by learners to access computers, leisure and various literacy tasks. Eye gaze technology allows individuals to use the movements of their eyes to operate a laptop, computer or high tech AAC device (e.g. language page set on GRIDpad device).

For our learners with complex regulation needs, specialist rooms, quiet rooms and open spaces have been built into the environment to ensure that each learner’s individual differences are being met, ensuring that learning can take place in various areas of the school. This also allows learners to access environments when they may feel overwhelmed or distressed, to support their wellbeing or to enable learning to continue in a different setting. Specialist rooms have various pieces of equipment installed, for example swings, music boxes (for therapeutic music) as well as other sensory equipment, including light panels and seating options to facilitate meeting sensory needs. Furthermore, the environment has been built with materials that prevent sound from travelling across the school, to protect those who may become overwhelmed by loud, unexpected noises.

Various areas of the school have been secured with access control, which allow members of staff with fobs to open doors or gates; this allows for safe transitions between different areas of the school as well as allowing learners who are experiencing distress, an uninterrupted space.

How Efficacy is Ensured through Training of Staff

The environmental adaptations and assistive technology are overseen by our Head of Strategy & Pastoral Support along with the Heads of School. Learners with physical & sensory disabilities have specialist assessments to determine how they can best access learning and the physical equipment and access methods they require. Learners all have access to regulation key rings as well as core board fringes which encourages them to make choices in terms of what environment/location/supports they would like to access. Regulation key and location fringes are embedded within the Well-being and Communication & Literacy curriculum and follows principles from the Self- Reg practices. All teaching, wellbeing and therapy staff have received basic training on sensory processing needs and regulation strategies and physical barriers to learning where appropriate. The school approach to coaching and supporting our teaching staff and therapists, alongside our CPD strategy ensures we continue to develop and grow our practice in this area.

References & Useful Websites:

Beauchamp, Fiona & Bourke-Taylor, Helen & Brown, Ted. (2018). Therapists’ perspectives: supporting children to use switches and technology for accessing their environment, leisure, and communication. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention. 1-15.

Burkhart, L. J. (1980). Homemade battery powered toys and educational devices for severely handicapped children. College Park, MD: Author.

Burkhart, L. J. (1982). More homemade battery powered toys and educational devices for severely handicapped children. College Park, MD: Author.

Burkhart, L. (2018). Stepping Stones to Switch Access. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 3(12), pp.33–44.

Copley, J., & Ziviani, J. (2005). Assistive technology assessment and planning for children with multiple disabilities in educational settings. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(12), 559-566.

Nguyen, T., Tilbrook, A., Sandelance, M., & Wright, F. V. (2021). The switch access measure: development and evaluation of the reliability and clinical utility of a switching assessment for children with severe and multiple disabilities. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 1-12. doi:10.1080/17483107.2021.1906961

Nguyen, T., Tilbrook, A., Sanderlance, M., Wright, V. (2018), “Determining the Reliability and Validity of the Novita Switch Access Solutions Assessment”, Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 60 (51), 34

Zorzi, S., Marangone, E., Giorgeschi, F., & Berteotti, L. (2022). Promoting Choice Using Switches in People With Severe Disabilities: A Case Report. SAGE Open, 12(1).

Marwati, Annisa & Dewi, Ova & Wiguna, Tjhin. (2021). Visual-Sensory-Based Quiet Room for Reducing Maladaptive Behavior and Emotion in Autistic Individuals: A Review. 10.2991/ahsr.k.210127.061.

https://nationalautismresources.com/school-sensory-rooms/

Rajagopalan A, Jinu KV, Sailesh KS, Mishra S, Reddy UK, Mukkadan JK. Understanding the links between vestibular and limbic systems regulating emotions. J Nat Sci Biol Med. 2017 Jan-Jun;8(1):11-15. doi: 10.4103/0976-9668.198350. PMID: 28250668; PMCID: PMC5320810.